Documenting my application journey and advice for PhD applicants

Published:

DISCLAIMER

All views below are my own, based on my application process, speaking to current PhD students during this process, and several helpful online resources, which I have linked at the bottom of this piece.

Your experiences may differ wildly from mine based on a range of factors, including the field you’re applying for, specific schools, the specifics of your profile, and timing – on this last point, I believe that unfortunately funding, and consequently competition for places, is expected to be tight in the coming years across countries. Moreover, this advice is geared towards U.S. PhD applicants, given I applied to U.S. programs.

Above all, I want to emphasize this is a human-centric process. Applying for a PhD, you’re applying for a job (replace the word “salary” with “stipend”), and like any job application, there’s no guaranteed outcome. You can have the ‘perfect’ application but still not get a place if there’s not the right research and personality fit with faculty. Conversely, you could have ‘gaps’ on your application; a questionable GPA, no formal research experience, less recognized affiliations; but a faculty member might see your potential and take a chance.

Objective criteria like published research and high GPA matter, so if you have the opportunities in front of you, take them. However, once you’ve maximized your credentials and refined your application to the best of your ability, it’s out of your hands. Shoot your shot!

SECOND DISCLAIMER

I’m writing this as I start my PhD program, so my perspectives will likely evolve. I’ll update this post or write future pieces to share updated insights.

The rest of this guide covers the following:

- Why I’m writing this guide

- My application journey

- Reflections and lessons – the key takeaways I’d share with prospective applicants

If you’ll humor me, I weave my personal narrative into this longer-form piece. If you’d prefer just the substance, I’d suggest reading the condensed version, which you can find in the navigation pane of my site.

Contents

- Why I’m writing yet another PhD application guide…

- The decision to apply

- Preparation

- Selecting programs and staying organized

- Faculty outreach

- Letters of Recommendation

- The GRE

- Statement of purpose

- Personal Statement

- Supplementary materials: CV, writing samples, and transcripts

- Submissions

- Interviews

- Decision time

- General advice and lessons learned

- Thank yous and acknowledgments

- Resources

Why I’m writing yet another PhD application guide…

There are a multitude of PhD application guides out there, so why bother writing another one?

Firstly, I couldn’t find any specific to Communication, with most guides written by STEM-oriented PhDs. To reiterate, my experience will not be universal to all Comms students and programs. However, if at least one aspiring Comms PhD reads this guide and draws some confidence or knowledge for their applications, I will consider that a success.

Secondly, I’m probably older than the median PhD applicant, coming into the program with around 10 years of research or professional experience. I can share the thought process of pursuing a PhD as a more experienced student, including pros and cons. If you’re wondering whether you’ve missed the boat on graduate study, you haven’t! However, you’ll need to make a more considered decision than someone straight out of undergraduate studies.

Thirdly, my credentials are far from perfect. The surface level polish of prestigious schools masks a patchy academic record, including a low 2.1 at undergrad (roughly equivalent to a 3.3 GPA), some 2.2s (the equivalent of C grades) in quantitative modules, and zero journal publications. Very little of my 10 years’ experience was in research-intensive roles. Yet I was able to compensate by communicating what truly matters – research potential – and had a couple of phenomenal programs and faculty take a chance on me. If you don’t have a perfect academic record, and are serious about research, don’t feel discouraged. Instead, take realistic steps moving forward to prepare yourself.

Fourthly, self-indulgence. In part this is a letter to my 18 year old, who wanted to a PhD, and would have been thrilled to do so at an Ivy League (or equivalent) university, but decided after about a month of undergraduate studies he wasn’t cut out for it. This was due to an entirely wrong perspective on what a PhD involved, which I held until about a year ago. If you’re an undergraduate student reading this, there may be lessons for you too. 18-year old Rehan, we got there in the end!

The decision to apply

On a sunny summer afternoon in Cambridge, MA, I sat across from my supervisor at a local ramen shop, debriefing my policy research role as it neared its end. It was July 2023, and I was about to return to the U.K., uncertain about my next steps.

“What do you want to do with your career?”, she asked.

“I love research, and I want to use that to move the dial in the tech industry for good,” I responded. “Maybe I can find another role like this one at a think tank, or research or trust & safety work in industry.”

“Have you considered a PhD?”, she interjected, suddenly smiling.

Internally, my initial reaction was no. I had thought about it, living with two PhDs that year, but had long considered it a dormant dream. I enjoyed the deep theoretical discussions with my roommates but also observed a dedication to research I wasn’t sure I could match. Did I have the attention span for research papers and textbooks? The work ethic? At undergrad, my friends used to joke that I must do my supervision assignments in my head on the walk back from lectures, because they never saw me working. Plus, I didn’t have the grades.

“Hmm, I’m not sure,” I replied cautiously, spinning some ramen onto my fork. “I’m not sure I’m super academic, and it seems like a big commitment. Couldn’t I achieve the same goals at a think tank?”

“I’ve worked with you for a year now. I can see that you want to make a difference, and you get things done. Academia is going to truly allow you to create the impact you’re seeking. It will give you the tools to push boundaries with new thinking, not just synthesize what’s already known.”

Thinking about it further, it made sense. In my policy role, I’d loved the flexibility and room to dive into complex questions, but also hit roadblocks. Often, I felt limited to regurgitating others’ work instead of contributing meaningful solutions. I also felt I lacked the credibility and expertise to drive original thinking.

A PhD would provide the tools, space and time for transformative projects while building genuine expertise in technology and governance. It aligned perfectly with my vision for a career: project-based work that was creatively interesting, with opportunities to write, advise and potentially teach. The flexible schedule and conferences were appealing bonuses. Yes, there were downsides – the low-income and five-year commitment are significant trade-offs. But on balance, it seemed a viable route to my dream career. The only question was whether I was capable enough.

Why not apply and find out?

Preparation

With my decision made in late July, I’d left it late for the fall 2025 cycle, but I didn’t have the luxury of waiting another year. Organization would be crucial, as there were a lot of moving parts, interim deadlines and dependencies on others. I quickly realized many of the programs I was interested in had a deadline of 1st December – my birthday – giving me exactly five months to get everything sorted.

Here’s what you need to figure out for a PhD application, and you’ll need to do each of these well:

- Having clear motivations for doing a PhD

- Demonstrating research capabilities through strong coursework, research experience, publications, and/or translatable professional experience

- Identifying your research area(s) and the questions you want to address

- Selecting programs to apply for, understanding requirements, and tracking deadlines

- Identifying faculty you want to work with and demonstrating research fit

- Researching program details: research centers/labs, coursework, stipend availability, and culture

- Distilling all the above into a well-focused statement of purpose (SOP) (~1,000 words)

- Crafting a compelling personal statement (~500 words)—required at most but not all schools/ Some schools instead ask for supplemental essays to specific prompts

- Choosing recommendation letter (LOR) writers and securing their commitment early

- Taking the GRE if required (increasingly falling out of favor)

- Preparing supplementary materials: CVs, writing samples and transcripts

- Post application – preparing for potential interviews

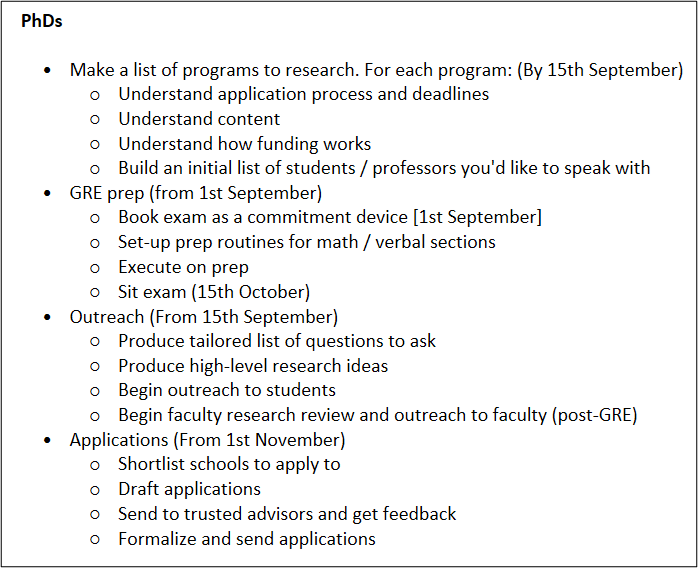

I created a high-level workplan that broke down into daily tasks, using target dates to stay on track for the December 1st deadline. You can find the resources I used to prepare for my application in the Google Drive folder shared in the resources section below.

Unique approaches I took

Speaking to current students: While it is common practice in certain fields to reach out to faculty before applying (more on this later), contacting current students is less standard but highly valuable.

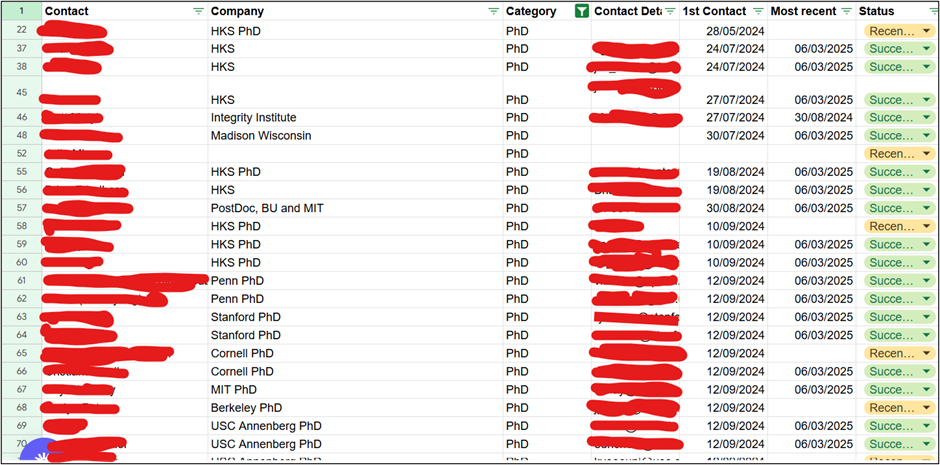

I’d highly recommend this approach for a few reasons. Students are more likely to respond (they’re busy but many are willing to help) and provide more candid responses. They are extremely well positioned to tell you which faculty would be good research and personality fits, and they may know who’s taking students in the upcoming cycle. These conversations also helped me to realize how supportive the PhD student community is – you’ll see from a screenshot of my contact sheet below an incredibly high response rate to my queries. On calls, people were without exception supportive and helpful – giving my additional confidence I could do this.

Two conversations stick out. In one call, I was dissuaded from applying to a program based on a student’s experience, which resonated with my own concerns, saving me time and application fees. In another, a student at another program suggested I’d have higher success chances if I pivoted to different faculty who’d value my professional background more. I didn’t take this advice, and am glad I stuck to my guns. However, being pragmatic, his advice was valid, and may have helped my chances on a program I ultimately was unsuccessful in applying for.

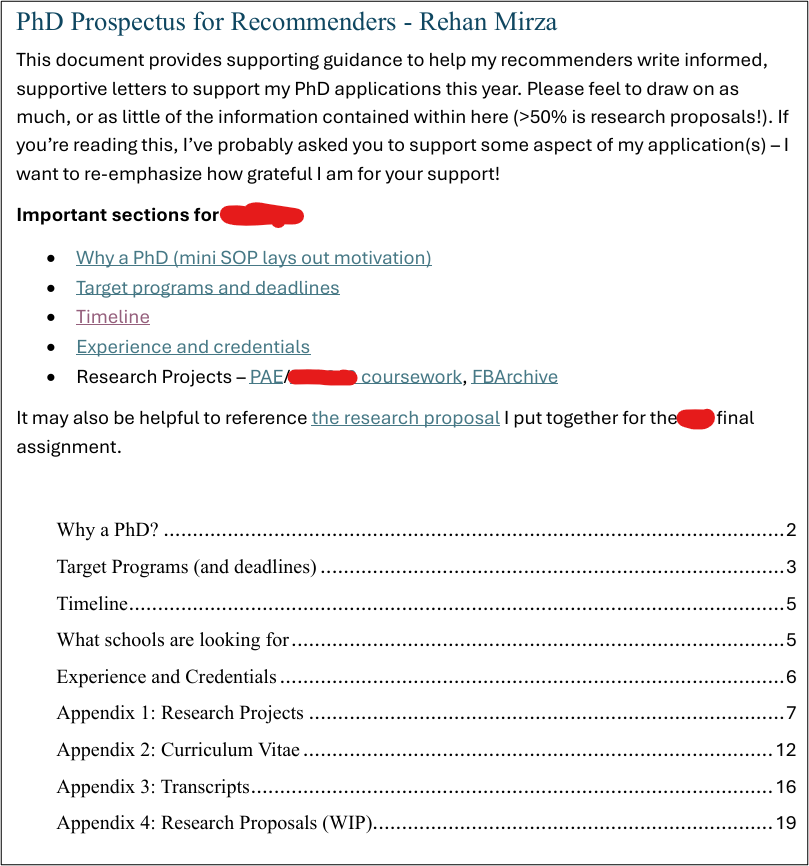

Writing a prospectus for recommenders: This isn’t unheard of but certainly isn’t universal. Your letter writers need to demonstrate your research and personality fit for each program. While many provide superlative commentary, it helps to substantiate this with details and evidence. If it’s been a few years, or your LOR writer teaches hundreds of students, their memory can be fuzzy.

Sending an information packet shows you’re prepared and serious while providing material to help them write the strongest letter possible. Just remember they’re busy – don’t overwhelm them with information like I did! I’ve included a template in the resources section and will cover LORs in more detail later.

Doing a ‘literature review’ of prospective faculty: Applicants who want to do a good job of demonstrating research fit with faculty will have to read their work. At the least you’ll have a decent knowledge of the methods they use, and the topics they are interested in. Reading abstracts is probably sufficient, but I took this a step further, reading through 3–5 papers from each faculty member I wanted to work with.

In practice, this was extensive work in a short time frame – with 32 faculty across 8 schools, I ended up reading 140 papers in a month! However, I’d say it was worth it. It helped me precisely communicate research fit in outreach emails and my statement of purpose, gave me practice reading research papers, and improved my understanding of topics including platform design, user behavior, and online political engagement. Plus, you’ll probably have longer than a month for this! I’ve included a template faculty research tracker in the resources section.

Selecting programs and staying organized

There are multiple valid approaches for selecting programs. I started by brainstorming the research questions I wanted to answer and identifying the fields that could help address them.

Starting with research questions

For example, one question I wrote down was: “How can we encourage users to break out of negative loops of consuming low-quality content?” This led to numerous associated questions:

- How are user interfaces designed to shape on-platform user experience?

- How are content delivery systems (algorithms) designed to shape user experience?

- How might changes to interfaces or algorithms affect user behavior?

- How do we define “low-quality content”?

- What are the negative impacts of “low-quality content” on individual and group levels?

- How do these impacts differ short-term vs long-term?

- When designing interventions, what is our intended outcome? For instance, reducing time on-platform or shifting to “higher-quality content” (however that is defined)?

- How do we measure intended welfare improvements?

- How do we balance welfare improvements against other considerations like user autonomy and commercial priorities?

- What are the political barriers and implications of potential interventions?

This exercise clarified that answering these questions required knowledge across multiple disciplines: information sciences, computer science, behavioral psychology, economics, political science, and public policy. Communication made the most sense to me given its interdisciplinary approach, though specializing in fields like political science or organizational psychology was another valid option. My litmus test became whether programs had at least three faculty members conducting relevant research who were taking students that year.

Another totally valid approach is to center on discipline first, then figure out suitable topics of interest within that discipline. If your passion is within a particular field, such as CS or economics, or you want to build methodological expertise, this is the way to go. Research is a collaborative endeavor, and there is room for both generalists with cross-cutting expertise and functional specialists.

Other key considerations

Following in the footsteps of successful alumni: I researched PhD alums doing interesting work in industry or academia and looked at what they had studied. This aligned with the fields I’d identified: communication, information sciences, social psychology, computer science, and economics.

Personal background fit: My background suited communication’s interdisciplinary approach. Without the strongest quantitative background, subjects like information sciences or political science were challenging but doable, while economics or computer science were out of the questions (and probably less enjoyable given I also enjoy qualitative work).

Institution and location: It is generally advisable to apply broadly, because PhDs are ultra-competitive. However, at my age and stage of my career, the PhD presents higher opportunity costs, and institutional prestige (unfortunately) matters for signaling. I was also more picky on location, generally sticking to coastal cities, but this is a personal choice.

Program structure varies significantly. Some programs pair you with faculty immediately, whereas others have you find an advisor after a year or two. Coursework requirements and teaching commitments also differ. Current students and program handbooks are excellent sources for this information.

Funding should be non-negotiable. This is a job, so you should receive a livable stipend. I actually didn’t apply to any New York City schools because I didn’t think I could make the stipends work with the cost of living, though others obviously can.

How Many Programs?

There’s no right answer here. I’ve heard everything from one program (where a supervisor essentially said “stay here for your PhD”) to 20–25 programs. I support the logic of applying more broadly given how competitive PhDs are, but would estimate each school requires at least 10 additional hours of work, researching faculty, personalizing statements, and completing applications.

I applied to 8 programs and could have stretched to 10. Around 10 seems like the right balance, though this depends on your priorities and circumstances. Don’t underestimate the costs – I spent around $1,000 on application fees and the GRE. 20 programs could mean $2,000! Please look into application fee waivers if you’ll struggle with the costs.

Stay organized

I maintained spreadsheets tracking deadlines, submission requirements, faculty of interest, and costs for each program, which I share in my resources section below. Make sure you are regularly reviewing these details so you don’t miss anything important.

Faculty outreach

Faculty outreach is one of the most confusing and anxiety-inducing parts of the application process for many people. For some programs (and faculty members) it is not required or actively discouraged, whereas for others it may be essential.

Why it can matter

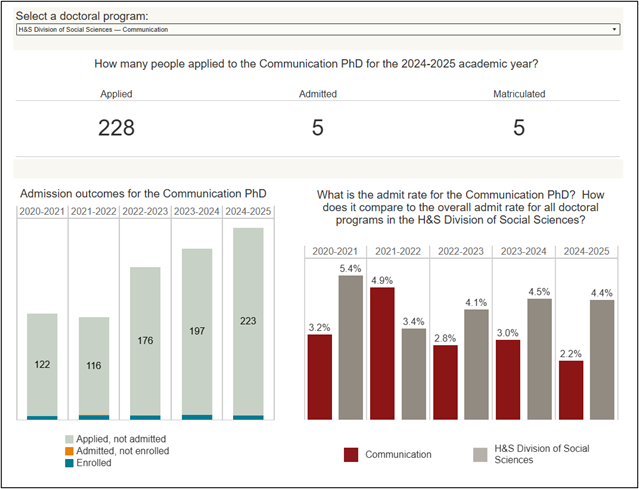

To understand why outreach can matter, let’s consider the selection process from a faculty perspective. Each cycle, faculty receive many multiples of applications for places. As an example, let’s take a look at Stanford’s admissions statistics for communication.

That’s an awfully large number of applications for an awfully small number of places! Even highly qualified candidates have to be turned away.

To filter even further, the faculty then must select students whose research interests align with faculty who have the capacity (and funding) to take on new students. Programs typically follow one of two selection models:

- A rotating committee of 3–5 faculty selects students for the program as a whole, not necessarily for themselves directly. They choose students who fit well with faculty known to have capacity and funding (e.g., Northwestern’s Media, Technology and Society program).

- Specific faculty members take turns selecting students they want to work with directly (e.g., Stanford’s Communication PhD program).

It’s early December, and applications are in. The committee or faculty member have sifted through and narrowed down from ~40 applicants per place to let’s say, ~3 applicants per place, for whom they have to establish research fit. Writing a strong focused statement of purpose that communicates this is certainly crucial, but in some cases, building a prior rapport with a faculty member through outreach can help them to bat for you.

Should you reach out?

Broadly, here are the reasons why it might be a good idea to reach out to faculty:

- Visibility: Faculty are primed to look out for your application amongst the masses

- Demonstrated interest: Some faculty appreciate the proactivity and engagement with their work

- Practical information: You can learn whether they are taking students that year

The two programs where I received admissions were the two where I had positive responses encouraging me to apply. Equally valuable, I learned certain faculty weren’t taking students, so I didn’t waste effort tailoring my application to them.

Here’s why it might not be a good idea to reach out faculty:

- Email fatigue: Faculty receive far more outreach emails than they used to, and some are irritated by the volume

- Perceptions of gaming: Some faculty might consider it as trying to game the system

More neutrally, some faculty might just ignore or forget your email, and it won’t affect your application at all.

As always research is key. Before contacting anyone, read their recent work extensively. Understand not just what they’ve studied in the past, but where their research is heading. Check their personal websites for clues about whether they’re taking students, their communication preferences, and their personality. Some faculty explicitly mention if they’re not taking students or prefer not to be contacted by prospective applicants.

On timing, there’s also not a clear answer, but earlier is generally better. Late summer is probably optimal as it can be quieter, though some faculty may be taking time off.

Basic structure of a cold approach to faculty

Dear Professor X,

I’m a recent graduate with a degree in biology from the University of Michigan, and I’m applying for a PhD in Biological & Biomedical Sciences this fall. I’d like to focus on mutant genetics, with particular interest in research questions related to the heritability of enhanced genetic traits, given recent advances in gene therapy technologies.

I’d be excited to work under your guidance given your groundbreaking work in this area, if you are taking on students this year. I particularly enjoyed reading about your recent paper employing computational methods to analyze genetic sequences associated with enhanced sensory abilities, and I’m interested in applying similar methodologies to understand the neurological basis of telepathic communication. This builds on my undergraduate research with Dr. Octavius on bio-mechanical interfaces, which approached neural enhancement from a more physiological perspective.

If you’re available, I’d love to chat further to learn more about your current research directions. Thank you for your time, and I look forward to hearing from you.

Kind Regards,

Peter Parker

What to include

- Brief introduction of your background and research interests

- Specific connections to their work (cite specific papers or projects)

- Clear question on whether they’re taking students

- Professional but personable tone

- Keep it concise – no more than 3–4 paragraphs

Avoid sending generic emails, providing excessive details, asking basic questions that could be answered through research, or being overly demanding.

Following up: One polite follow-up after 2–3 weeks is acceptable if you haven’t heard back. After that, let it go. Faculty are overwhelmed during application season. Even if you don’t get responses, still mention these faculty in your application materials. Lack of response doesn’t mean lack of interest – they might simply be too busy to respond to everyone.

Letters of Recommendation

Strong letters of recommendation can swing things in your favor, while poor ones can break your application. It’s crucial to carefully choose your recommenders and support them with the information needed to write the strongest possible recommendations.

Choosing the Right Recommenders

Ideally, you want three academic recommenders who are recognized in your field and can speak to your research potential. If you’re coming from industry like I was and have been out of academia for a while, you can include a letter from a professional supervisor. Either way, choose people who can speak to your research potential—your analytical capability, intellectual curiosity, thought leadership, organization, or capacity to own projects.

Equally important is the person’s relationship to you. Ideally, they know you in a research capacity and can point to specific projects they’ve supervised you on. This is easier if you’ve worked as a research assistant or completed a thesis with faculty members. If you’re taking a class with a prominent faculty member you’d like as a recommender, actively participate, demonstrate intellectual curiosity, and signal your PhD intentions during office hours. This may translate into research opportunities or form the basis of a solid recommendation.

My recommender mix

My three recommenders were:

- Academic reference (gold standard): A recognized name in my field who had supervised a prior thesis and could speak to fundamental research capabilities

- Academic reference (methodology focus): A professor I’d worked with as a research assistant years earlier in a different field, who could speak most directly to my quantitative abilities

- Professional reference: An experienced practitioner running the research center where I worked, who had supervised me as both a course assistant and policy researcher and could speak to research capabilities plus professional attributes

When and How to Ask

Ask early – at least three months before your earliest deadline. If possible, approach recommenders in person or work with their assistants, as emails can be easily missed. State your goals clearly, including the field and number of programs you’re applying for, and explain why you want them specifically to write your reference. Provide an “easy out” in case they can’t write a strong letter, as a lukewarm recommendation could hurt your chances.

Don’t be afraid to ask! Faculty write references for multiple students every year and consider it part of the job. As long as you’re polite and have a sufficiently positive relationship, feel empowered to ask for their support.

The Recommender Prospectus

As mentioned earlier, I sent my recommenders a comprehensive packet containing:

- Mini statement of purpose

- List of programs with key details about each

- Specific projects we’d worked on together with details they might have forgotten

- My CV and transcripts

- Talking points about my strengths and growth areas

- Deadlines and submission instructions

Was this overkill? Probably. But it showed I was serious and provided concrete material to reference in their letters.

Managing the submission process

Once you have their agreement, send reference requests through admissions portals as soon as possible to provide flexibility on their end. Send gentle reminders two weeks before deadlines, then again one week before if needed.

Have a backup plan! For my Oxford master’s application years ago, one recommender submitted a day late despite communicating he wouldn’t make the deadline. Some programs provide leeway for late submissions, but Oxford was unfortunately quite strict. Having a backup recommender identified can save you significant stress.

The GRE

The GRE is increasingly falling out of favor, but some programs still require it. Check each program’s requirements carefully. Many Communication programs have dropped the GRE requirement entirely, especially post-COVID. If it’s optional, think carefully about whether your scores would strengthen or weaken your application. Sometimes, a strong quant GRE score could help address questions around quantitative ability from your transcript.

If you do decide to take the GRE, don’t overthink the preparation. The exam tests fairly basic math(s) and reading comprehension. A few weeks of focused study should help you brush up with these concepts and the style of exam questions. I’d recommend GregMat for prep materials, and get a few practice papers in. I focused mainly on the math(s) concepts and flashcards for vocabulary , learning a couple of hundred extra words I was unfamiliar with.

I’d take it early enough so you have time to retake if needed, and that will also help you be more relaxed going in. GRE scores are valid for five years, so if you’re planning ahead, you can take it during undergrad or early in your career. I’ve actually taken the exam twice – once in 2017, two years before I first applied for my graduate degree in the U.S., and once in October last year, two months before applying for my PhD. It may be declining grey matter, but I actually did better the first time around with less focused prep, probably because I was more relaxed going in.

Ultimately, don’t stress about it – perfect scores look great, but they’re rarely the deciding factor in PhD (or masters) admissions.

Statement of Purpose

This is the most important document in your entire application – your sales pitch for why you belong in their program.

Structure and key components

Opening: Start with a clear, compelling hook that establishes your research interests. Avoid clichés like “Ever since I was young…” Instead, ground your opening in a specific research question or intellectual puzzle that drives you.

Research experiences: Detail your research or professional experiences, focusing on what you did, what you learned, and how these experiences prepare you for doctoral study. Be specific about methodologies, findings, and your individual contributions. Don’t just list experiences, but analyze what they taught you about the research process.

Research interests: Articulate your intellectual interests clearly, connecting them to broader theoretical frameworks and current debates in the field. Show you understand how your interests fit within existing scholarship while identifying opportunities for original contribution.

Program fit: Demonstrate specific knowledge of the program and faculty. Name specific professors and explain how your interests align with theirs. Reference their recent work and explain how you might contribute to their research agenda. This section should be different for every program you apply to.

Future goals: Briefly outline your career trajectory and how a PhD from this program will help you achieve your goals. Be realistic but ambitious.

I’ve included a sample copy of my own SOP in the resources below.

Some common pitfalls to avoid include:

- No clear throughline or narrative arc – keeping things simple, I’d recommend a chronological format

- ‘Telling, rather than showing’ your capabilities or interests. Saying “I’m passionate about researching mental health”, or “I have a strong quantitative” background doesn’t achieve anything and wastes valuable space.

- Focusing on non-academic experiences without connecting them to research potential

- Generic statements that could apply to any program

- Overly personal stories that don’t relate to research

Every sentence should be focused on one of the following:

- What research you’re interested in, grounded in specific topics and research questions

- What research (or professional) activities you’ve conducted, with a focus on research questions and methodologies

- Specific contributions you’ve made through thoughts and actions

- What you’ve learned from these activities, and reflections for future work

- Which faculty you’d like to work with, grounded in specific topic and research questions

- Optionally, what coursework you’d like to study, grounded in specific topics and research questions

- What you’d like to do in future, grounded in a how a PhD will enable you to get there

The writing and revision process

Start drafting early, ideally late September or early October for December deadlines. Your first draft will not be good, and it’s going to take many iterations. Make sure you read other statements from successful students in your field, and a few different guides, some of which I’ve linked below.

Please, please, please share your statement with mentors and friends, ideally who are current PhDs, and encourage them to be candid. Their feedback will be invaluable, as they’ve been in your position, and can notice blind spots you’ll miss. I had a call with a friend where she took 90 minutes to convince me why I should change the structure of my SOP amongst other things. Though I was initially defensive, I woke up the next day and realized she was right!

Personal Statement

One academic YouTuber describes the personal statement as “a trap” (video linked in the resources below). I wouldn’t entirely disagree.

While SOPs focus on research interests and academic preparation, personal statements typically ask about your background, challenges you’ve overcome, and personal motivations. Common prompts can include describing challenges you’ve faced, discussing commitments to diversity and inclusion, or explaining how your personal background informs your research interests. Some schools, like Stanford or Penn, may ask targeted supplemental questions you can treat similarly to the personal statement.

While this is a rare space for self-expression and a chance for faculty to assess your personality, the personal statement should still answer the same fundamental question as every other part of your application: “Does the applicant demonstrate research capability and potential?”

I really enjoyed writing my personal statement. I took it as an opportunity to showcase my writing skills, share my personal journey, and explain how doing a PhD would help me achieve my potential. However, looking back, I’m not convinced I did the best job demonstrating my capabilities and motivation for being a researcher. I over-indexed on personal history and under-indexed on how that history would shape my research goals moving forward.

I also would have written a much worse statement, one that could potentially derail my application, without some candid feedback from my friend on the 90-minute call I mentioned earlier.

Focus on experiences that genuinely shaped your intellectual development or research interests. Connect personal experiences meaningfully to your academic trajectory.

Avoid these pitfalls:

- Unfocused personal stories: While it is OK to share personal struggles, these should have a clear connection to your research goals

- Unprofessional content: Avoid stories that make you seem unreliable or unsuitable for academic work

- Controversial topics: Be cautious with political identity or religion unless they directly relate to your research interests. If you do address these topics, do so thoughtfully, because you never know the views of the person reading your statement

Share enough to seem genuine and three-dimensional but always connect personal experiences back to your academic goals. The admissions committee wants to understand you as a person, but they’re ultimately evaluating you as a potential researcher and colleague.

Supplementary materials: CV, writing samples, and transcripts

Academic CV formatting: An academic CV is different than a professionally resume. Unlike industry resumes, academic CVs should be longer and include everything relevant to your development as a researcher, including research methodologies.

Key components:

- Education (feature at the top)

- Research projects and positions with detailed descriptions

- Professional experience (keep it succinct, and translate it to research potential)

- Publications, presentations, and conference activity

- Technical and methodological skills

- Teaching or course assistant roles

- Service, leadership, and hobbies (this is still a human-centric process!)

Writing samples: These should ideally be academic pieces demonstrating both strong writing and methodological sophistication. Single-author published articles (or excerpts) are the gold standard, but undergraduate theses, graduate coursework, or professional research reports can work. Choose pieces that showcase strong writing skills and methodological applications relevant to your proposed research area.

Transcripts: Follow instructions carefully – most schools accept unofficial transcripts for initial review, but some may want official transcripts up-front. On another application to Oxford (…separate to the one I mentioned earlier), they threw out my application because I had submitted unofficial transcripts rather than the official ones requested.

Please note that although grades are an important part of the application, they are not the single most important part. Strong grades clearly demonstrate research potential, and evidence of attainment in specific courses may be considered necessary academic preparation for certain programs, especially ones with quantitative methodologies. However, you can build a contextual picture around less-than-perfect grades, for instance through an upward trajectory over time, or through subsequent research experience. Please also feel empowered to provide contextual information around grades if present.

Submissions

After you’ve prepared all the required materials, and carefully submitted them, your application is done! Take some time off in December to celebrate, and don’t stress about hearing back!

Interviews

Not all programs interview candidates, but those that do typically notify students in December or January. Formats can vary – I can only speak to my own experience, which involved panel interview with my potential advisor and the selection committee chair, followed by a 1:1 chat with the potential advisor.

Preparing for interviews

I’d recommend preparing for the following questions:

- Why a PhD (and why now)?

- Research projects – be prepared to discuss any research mentioned in your SOP in detail, including research questions, methods, findings, and your specific contributions and learnings

- Research interests – have a clear vision of your proposed research area which you can clearly articulate, including how you hope to contribute to existing knowledge

- Which faculty members you see yourself working with, and how your research can align with them

- How the specific program serves your research goals

- Methodological interests

I’ve included a template to prepare for potential questions in the resources folder.

Framing

Equally important is your mindset around the interview. See it as a chat with someone who is an expert in your field, rather than a test. View yourself as a potential contributor to this program and the advisor’s work, not just a student. Remember, you’re evaluating fit as much as they are. Stay humble but confident – you belong in this conversation, or you wouldn’t have been invited.

The first of my two interviews (the panel interview) was quite stressful, partly because I received a notification about an update from another program just five minutes before it started! I definitely stumbled over a couple of questions due to nerves, but ultimately I think my preparation carried me through. In contrast, the second interview was amazing – by this point I had an offer in hand so I could be relaxed, but I also approached it as an engaging conversation about research I was genuinely excited about.

To reiterate, enjoy these opportunities to talk with brilliant people about ideas you care about – with some luck, you’ll be speaking to them for the next few years!

Decision time

Sometime between January and April, you will know where you stand.

If successful, congratulations! Take your time to carefully consider offers. Visit if at all possible – you’ll be there for 5–6 years, and there are intangibles you won’t pick up unless you’re there in person. I got a fantastic vibe from the community at Penn when I visited. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to visit the other school I got into due to family commitments, which left an incomplete picture for comparison. Having follow-up conversations with potential advisors and current students was also helpful in making my decision. Don’t be afraid to ask detailed questions about funding, expectations, and program culture.

If you have to decline other offers, do so professionally. People have invested significant time in evaluating your application and offering you a spot, so it was important for me to decline gracefully and express gratitude for their show of faith. There may be opportunities to collaborate with faculty at these programs in future.

If unsuccessful, I’m sorry – it sucks after putting so much effort into applications. But you’re not back to square one if you reapply. You have the another year to build research experience, strengthen your application, and develop clearer research focus.

If you’re waitlisted, don’t give up hope! I got off the waitlist for my previous masters program at Harvard, so it’s not an impossibility. You can send brief updates to the admissions team if there are significant changes in your situation (e.g., you can now bring funding with you).

General advice and lessons learned

Preparation is key.

Most elements of a strong application, including all the ingredients of a strong SOP, are the result of months if not years of work beforehand. Once you decide you want to do a PhD, make a plan and stick to it. If you’re early in your career, I’d give yourself a runway of at least 18 months to get the needed pieces together.

Consider getting professional experience.

There will be mixed opinions on this (and obviously I have my own bias), but I genuinely think a couple of years in a setting outside academia could be invaluable. For instance, working in consulting helped me practice research methods including quantitative analysis, semi-structured interviews, and surveys, while teaching me important skills that I would sum up as ‘professionalization’ - how to structure workplans, turn around work under tight deadlines, and produce materials to professional standards.

Another formative experience was volunteering in the rural Eastern Cape in South Africa, which helped me to appreciate how cultural context and identity could influence belief formation and practices, making me a better conceptual thinker. Take time out of the classroom, whether in the summers between school or in the years after.

For those of you with more professional experience, it is an asset, not a liability. Frame it in terms of research potential, as both analytical and professional skills translate well to academic contexts.

Details matter.

A key component of professionalization is paying attention to them. When you’ve done some great research, it’s quite conceivable that you get rejected from a journal not because of the quality of your work, but because you didn’t meet the journal’s standards or messed up your references. You need to take the same care with your application. Proofread everything multiple times. One or two typos probably won’t sink your application, but misspelling a professor’s name or mentioning the wrong school definitely will.

Focus on process, not outcomes.

Control what you can control – the quality of materials, the thoroughness of your preparation – and let go of what you can’t. And once you’ve submitted, please stay off GradCafe! It’s not a good place for your mental wellbeing. Any incremental informational benefit you get will be massively outweighed by people wondering why we haven’t heard back from USC yet when this time last year, they had released decisions a week earlier. It’s not worth it.

Consider this a life decision.

The time commitments and opportunity costs are too significant to just treat this as getting another degree, especially if you’re older or already have personal responsibilities. Make sure you understand what you’re signing up for, and where it’s taking you.

Build a community around you to support you on your journey.

You can’t go through this process or work in academia alone. Success depends heavily on relationships and community. Find your people, who will support you both critically within the field, and emotionally outside of it.

If you’re an international student, don’t be afraid to apply.

I applied as an international (admittedly from a privileged country), and don’t think I was hindered at all in my applications. Despite everything going worldwide, know that the academic community genuinely welcomes the diversity you bring. I won’t speak directly to visa complexities, as these are highly personally contextual, but I would say it’s all the more important to be organized as an international applicant given the additional steps in moving to a new country.

Trust the process and trust yourself.

Imposter syndrome is real and pervasive in academia. If you’ve done the work into putting together your application, you’ve already demonstrated the intellectual curiosity and capability that belongs in graduate school. The fact that you’re even considering a PhD suggests you have something valuable to contribute to human knowledge.

Remember why you started.

In the stress of applications, deadlines, and rejections, it’s easy to lose sight of what drew you to apply for PhDs in the first place. Hold onto these motivations; they’ll carry you through the process and remind you why this journey is worth taking.

The path to a PhD is rarely linear, and everyone’s story is different. Whether you succeed this cycle or need to try again, the skills you develop, relationships you build, and self-knowledge you gain through this process have value beyond any single outcome.

You’ve got this.

Thank yous and acknowledgments

To my supervisor, Laura, for giving me the confidence to apply when I needed it.

To Nancy, Latanya, and Jolene, for writing the letters that got me in. To Max B. (my MVP!), Josh, Leonie, Kevin, and others, for helping ensure those letters got in on time.

To Kevin, Jim, Sharad, Jen, Shiv, Theo, Gaby, Brian, Ruru, Swapneel, and many others, for their support and guidance throughout this process. Special thanks to Sid, Michelle, and Megan, for taking time to do multiple reviews of my application materials, offering much needed candid feedback, and tolerating my stress on multiple occasions!

To Max S., Ke, Viswanath, Chloe, Ryan, Cid, Cristiana, Suyash, Lei, Eun, Daniel, Achi, Nusrat, Matt, and Paul for taking the time to share insights about their respective programs.

To my grandparents for giving me that extra motivation to publish research, knowing I can send it to you to make you proud.

And most importantly, to my parents for their unwavering support during this process, for having my back, and for always allowing me to follow my own path despite an uncertain future.

Resources

Shared materials: All templates and tracker tools mentioned in this guide are available in my Google Drive folder. Please feel free to adapt these for your own use.

Additional guides that helped me:

- Dr Swapneel Mehta’s SOP guide – shoutout to Swapneel who’s an amazing person invested in helping others get their start in research. He sent me a bunch of other resources during my own application process, and I know he helps several students each application cycle

- Dr Lucy Lai’s guide to PhD applications in STEM

- Dr Lucy Lai’s SOP video guide

- Dr Vael Gates’s guide on PhD Applications

- Dr Darren Lipomi’s guide to getting into graduate school in science and engineering (PhD)

- Dr Angela Collier’s guide on why “your personal statement sucks”