Perspectives and Frames

Published:

You may have heard of the parable of the blind men and the elephant. Several blind men discovered that an elephant, an animal unfamiliar to them, had recently come to their village. Going to investigate, one by one they felt different parts of this strange creature. One villager touched its tusks, another its trunk, another its ears, and so on.

Coming together, there was considerable debate around what this animal was. “This beast is just like the spear I crafted for hunting,” exclaimed one villager.

“No, it’s like a fan,” responded another, who had touched the elephant’s ear.

“You’re both talking nonsense,” retorted a third villager who had touched the trunk, “It’s clearly a snake.”

“It may have the same shape as snake, but what you were feeling was actually a rope,” chimed in a fourth, who had touched the tail.

The villagers almost came to blows, each leaning into their own limited perspective. It took a sighted person who could see the animal as a whole to reveal the truth to them. The moral of this parable is that although we draw from our own perspectives and experiences, they may be limited and not tell the whole story.

I’d add a small addendum to this parable: initial appearances can be deceiving. Those of you who have been fortunate enough to touch an elephant will know that it is in fact hairy, when from afar it looks like it may be smooth and scaly!

Meeting an elephant in South Africa!

Meeting an elephant in South Africa!

Understanding Polarization

Polarization is a topic I’d like to cover in my research. Downstream of the immediate impacts of platform design and broader moderation and safety practices, I’m interested in the extent to which technology reinforces differences today, and its potential to bridge those differences.

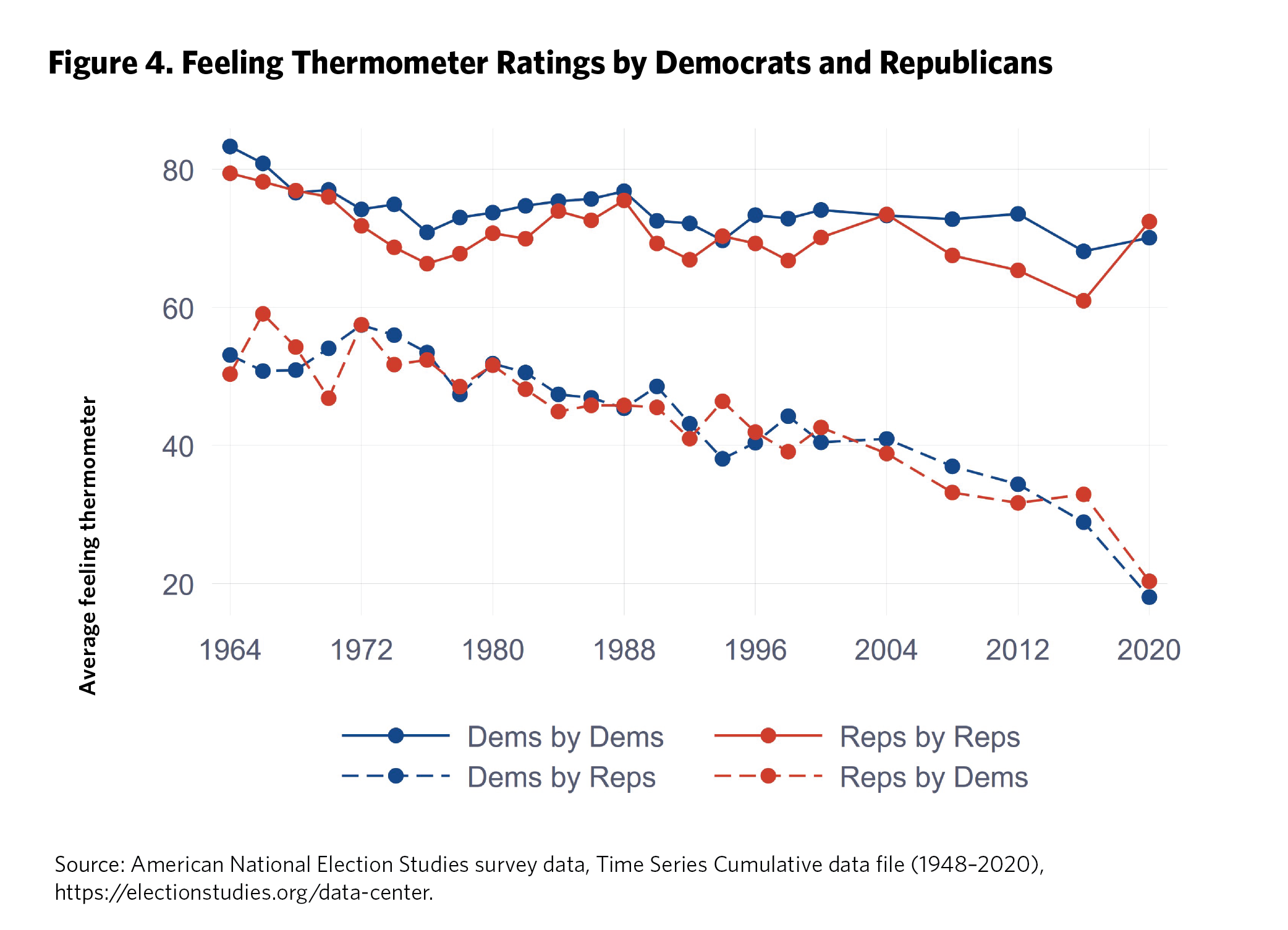

Observing the world as a layperson (rather than a trained academic who has yet to dive deep into the research), the world seems more divided than ever. Politics is one obvious arena where this appears true, and it’s relatively tractable to study. While there’s been a much longer-term decline in positive sentiment toward politicians (in the US context), this has accelerated in the social media age. I’m careful not to confuse correlation with causation—there will be multiple competing and potentially interacting explanations for this.

I guess I have the next five years to answer questions like, “Is the world indeed becoming more polarized, and in what domains?”, “Have platform designs and structures contributed to this, and how?”, and “to what extent is disagreement needed for healthy discourse?”

Right now, let’s just take the fact that there is increasing polarization in the world today as a “stylized fact” and run with it.

Feeling Thermometer Ratings by Democrats and Republicans

Feeling Thermometer Ratings by Democrats and Republicans

Why We Disagree

Returning to our parable, everyone has their own knowledge, perspectives, and values drawn from their sense of self and lived experience: their own “part of the elephant.” We’re naturally inclined to weight our own knowledge, perspectives, and values higher than those of strangers. And so we get disagreements.

These disagreements are amplified in the global, connected world we live in today. For hundreds, if not thousands of years, people moved around and communicated, but slowly. Most of us lived, grew up, and died in the villages, towns, or cities where we were born, alongside people we’d known our whole lives. Over generations, communities developed value systems, ways of doing things, and interpretations of the world. Probably because they worked for that time and place.

Then comes globalization. My family moves from India to the UK in the mid-90s. As immigrants, we preserve many aspects of our culture and ways of doing things. But other things change. Some superficial: fish and chips, pasta, and chello kebab koobideh are welcome additions to our diets. Others less so: I imagine I would have retained far less of an ‘individualist’ mentality had I grown up back in India with a large extended family.

The advent of the internet and social media supercharges this, enabling not only the spread of people, but rapid spread of ideas. Millions (if not billions) of people will still grow up, live, and die in the villages, towns, or cities in which they were born. But with a smartphone in their pocket, a veil has been lifted. Language barriers aside, a villager in Madhya Pradesh could theoretically hold a conversation with a farmer in rural Ohio. More pertinently, there is ongoing exposure to new ideas, with an admittedly Western bias in the direction of information transmission.

The Promise and Peril of Connected Ideas

In some sense, this global ‘melting pot of ideas’ offered by global connectivity offers promise. In a marketplace of ideas and values, in theory, those that are most appealing should win out. However, I recognize this is a gross oversimplification.

What constitutes “good” ideas and values is inherently subjective and may vary by context. Even if we were to agree on these, changing perspectives doesn’t come without severe costs to both individual and community identities and cohesion. Not to mention a deep skepticism, probably borne out in outcomes, that the “good” ideas will win out. Instead, we’re more likely to see the ideas that command attention through algorithms and related content delivery systems (e.g., Reddit upvotes) win out.

Technology (and migration before it) has improved lives in so many ways, but it opened Pandora’s box on conflict. People with vastly different perspectives will inevitably come into contact with each other, and we have to learn to live with each other.

The Power of Frames

One helpful mechanism to think through these issues is the lens of frames. Let’s take a supposed objective narrative truth—a man steals a loaf of bread from a supermarket. There are witnesses, including the shop’s bodyguard, who manhandles our thief, throwing him out of the shop and calling the police.

We mostly all live in societies where we agree that stealing is a crime. And that stealing is bad. But the different frames through which this event is viewed can be enlightening:

- Is our Jean Valjean a dangerous criminal?

- Is he a helpless individual trying to feed himself when no other avenues exist, taking resources he needs from a faceless corporation who won’t know the difference?

- Is the bodyguard just doing his job, or being overly hostile?

Your interpretation depends on your values, worldview, and the many layers of context not present in this simple account. Different interpretations of “objective reality” as we see it contribute to disagreements. That’s of course assuming we are shaping the frame for ourselves, when this is as much on the message deliverer as recipient.

And I also acknowledge that it’s not so simple to just flip the frame, with it often being deeply embedded in identity and core beliefs. On a lighter note, I’ve often been told to frame an interview as a conversation and not a test—and I advise others to do the same. But it’s not that easy to just believe this. Your head may say, “Don’t worry, this is a casual conversation!” But then why is your heart suddenly beating at 150bpm and your voice coming out shaky? Because you haven’t internalized that frame, and the core beliefs underlying it.

Building and deconstructing frames requires repeated exposure—something that social media companies, traditional media, and the influencer class understand well.

Moving Forward

By coincidence, as I was putting together this post, a former classmate got in touch, introducing me to some great work being done by Professor Erica Chenoweth and Professor Julia Minson at the Harvard Kennedy School on the very topic of disagreement. I’m excited to read up further on their work (and potentially share my thoughts in a future blog post). This is also a wonderful demonstration of how the blog is already paying dividends!

We’re all walking through our own realities, each with our own piece of the elephant. In solidifying my understanding of the theory behind disagreement, in turn I hope to understand how we can improve technological designs, and the governance processes that surround them, to help us see the whole animal together.